Verónica Pérez, Social Pedagogue, trainer and consultant, Associate with Jacaranda Development. Simon Thomas Johr, social pedagogue at Adoption and Fostering Recruitment and Training Team, Staffordshire County Council.

The aim of the paper is to understand how social pedagogy could be integrated within the professional social care field in the UK. It looks at social pedagogy relationship with social work through the unique experience that social pedagogues from different parts of Europe[1] had during the Head, Heart, Hands programme (HHH)[2], led by The Fostering Network. The programme aimed to demonstrate how introducing social pedagogy into foster care could have a positive impact on British fostering services. Social pedagogy strives to understand the sociological context and how this can influence the professional practice, impact our and others thinking and actions. The common thread is to explore the encounter of the two cultures that happened throughout the national programme and the learning and reflections that stemmed from it. To enthuse and benefit the wide range of professionals that work in the field of social care in general and fostering in particular, providing some ‘food for thought’ and concrete ideas on how social pedagogy can be integrated with social work to contribute to improve the quality of care in the UK.

NOTA:

Artículo en dos versisiones. Versión original en lengua inglesa. Versión en lengua castellana en Pedagogía Social y Trabajo Social en el Reino Unido: El encuentro de dos culturas visto desde una perspectiva europea continental

The starting point of the paper is to define social pedagogy in the context of the HHH programme; then it looks into the different social backgrounds in childcare for the two societal models concerned, reflecting upon some of its similarities and differences, as well as the different levels of professionalization in childcare in both traditions. Following outlines the findings that could support the merging of the two ways of working, to reinforce some current social work practices and offer new understandings for enhancing the quality of care in the UK.

This article findings will be complemented with a future paper that will be focusing on the empirical aspects and learnings of the HHH programme: ‘Social Pedagogy in the UK. An experience in Fostering. Reflections on the learning from the Head, Heart, Hands Programme’.

Social pedagogy and social work have in common that they are professions that attract vocational practitioners with a strong advocacy for social justice; often the work is a ‘calling’. There is an ethical motivation in joining the profession in order to make a difference in society, in making the world a fairer one.

The HHH programme’s social pedagogues definition of social pedagogy is based on the belief, understanding and knowledge that one can positively change or influence disadvantaged situations through educational methods. Within those educational methods used, the practitioners are aware of themselves being the main ‘tool’ in their work. This requires to be critical and self-reflective, to be aware of their own values, beliefs and their own emotional triggers. This means that the social pedagogues have a consistent and clear Haltung, which is not only part of their individual professional life, but also a part of the pedagogues’ personality. The German word Haltung “roughly translates as stance, ethos or mind set and refers to the extent to which a person guides their actions by their ethical orientation and lives their values in the everyday” (Eichsteller & Holthoff, 2011). Haltung describes how our actions and thinking is guided by our convictions and also means that the practitioner needs to be congruent / authentic in order to be credible. A social pedagogue will try to intervene as little as possible, but as much as needed by gaining an understanding of the client’s life-world (Thiersch, 2005). Under this description, the pedagogue aims to work in a strength-based manner, which empowers the client, and uses a holistic approach, which considers the whole person as well as the system around them. Following this understanding, the social pedagogue would have mutual respect, trust, unconditional appreciation, believing that all human beings are equal with rich and extraordinary potential and consider them competent, resourceful and active agents. There is an awareness of the wider system and culture we are in, and we see the work in interdependence with society.

In relation to the relevance that the wider system is given in social pedagogy, the article will now explore the main characteristics of childcare in Britain, in contrast with those in continental Europe.

“There can be no keener revelation of a society’s soul than

the way in which it treats its children.”

Nelson Mandela

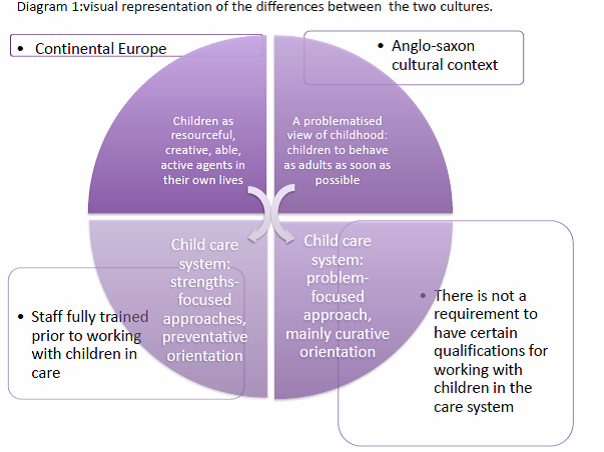

There are fundamental similarities by which continental European societies look after their most vulnerable children and young people. The United Kingdom has a long tradition in social work while a tradition of social pedagogy was also developed within continental Europe. In both, safety and wellbeing are at the centre of legislation and working practice. At the same time, there are differences in how children and young people are socialised and educated in continental European countries and what is considered the mainstream approach in the United Kingdom. These differences are primarily related to different social constructions of the ‘image of the child’. The latter refers to what kind of value children have in their society and which expectations and aspirations they live under. The attention paid to this idea has varied, for example, the sociology of childhood is important in some fields but rarely acknowledged in others, including policymaking. The image of the child in a determined place and time is a social construct, “always present and influential, but in policymaking, they are usually implicit, and therefore not discussed” (Moss, P. 2010).

To understand the different cultural views of the value society places on children and young people it is important to go back to the industrial revolution to trace the start of changes in how infancy/childhood are understood and viewed in modern Europe. This is closely linked to the development of formal education for children in different countries.

As the country where the irreversible transformational process of industrialisation started, the United Kingdom experienced great social and economic changes that brought up a new range of social problems, some of which affected mainly children and young people. These included child labour (Griffin, 2016), juvenile crime (White, 2016), poverty – especially among the working class – and orphanhood (Richardson, 2016). Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, new thinking emerged in continental Europe. Schools and formal education spread, and a number of philosophers and educators started to look at the aims and essence of educating the young, focusing on the nature and needs of children, and developing a progressive holistic understanding of growth and learning. One such thinker and philosopher was Jean-Jacques Rousseau. In his book “Emile or On Education” (1762) Rousseau explored the impact of socialisation and formal education on children’s ‘inherently good nature’ (Doyle and Smith, 2007).

Education and childcare in continental Europe were constructed and guided by principals such as individual agency, freedom and self-discipline (Entwistle, 1970). Social pedagogy was one influence in this development. Educators, politicians and social reformers have since built upon these developments which focused on the following: the idea of considering children as active agents in their development; the need to understand each child as a whole being; the importance of appropriate environments where they can develop to their full potential; and the vital role of an individualised and holistic approach to children rearing on the children’s overall wellbeing and achievements. Notions that today are considered as essentially social pedagogical, influenced how education and childcare were constructed in continental European countries.

This cultural shift was part of the construction of an image of the child as resourceful, creative, active, and able; of children as active agents in their own lives, being respected for their concerns as well as their skills, contributing to their ‘sense of agency’ (Stein, 2007). In the newly formed welfare systems and child care services, these views meant the prevalence of strengths-focused approaches, with a preventative orientation at their base. An example of this can be found in the work of Loris Malaguzzi, founder of municipal early childhood centres in Italy, which had at their heart a pedagogic philosophy for the early years that conceptualised children as ‘rich’, competent and active agents, arguing that “the child has ‘a hundred languages’, a hundred hands, a hundred thoughts, a hundred ways of thinking, of playing, of speaking” (Malaguzzi, cited in Edwards, Gandini and Forman, 1998; as cited in Moss and Cameron, 2011: 37).

As used in continental Europe, the word ‘pedagogy’ relates to the overall support of and for children’s development, whereas the ‘social’ component refers to society’s role and responsibility in this task. In pedagogy, caring and educating in its formal and informal meanings, meet each other, they are intrinsically related.

“To put it another way, pedagogy is about bringing up children, it is ‘education’ in the broadest sense of that word. Indeed, in French and other languages with a Latin base (such as Italian and Spanish) terms like l’éducation convey this broader sense, and are interchangeable with expanded notions of pedagogy as used in Germanic and Nordic countries” (Petrie et al, 2009: 3).

This view of the child, influenced by a more social pedagogical thinking, can be contrasted with what has been generally prevalent in Anglo-Saxon cultural contexts, where a more problematised view of childhood has prevailed, with children considered as different and having to behave as adults as soon as possible. When in the care of the state, or coming from economically and socially deprived environments, children are commonly seen as traumatised, handicapped and even delinquent. A view that creates a problem-focused approach within formal education and institutionalised care environments, with a mainly curative orientation, that is, to restore children/young people to their natural, obedient self (James and Prout, 2015).

British legislation of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which still influences modern-day legislation, reinforced the fact that children:

“were not ‘free’ agents; drew attention to the child-parent relationship with the latter being expected to exercise control and discipline; and emphasised the danger of those in need of ‘care and protection’ becoming delinquents” (Walvin, 1982 and May, 173; in James and Prout, 2015: 43).

The emphasis in residential and foster care in the UK is often to keep children safe and healthy, with the main aim to equip children with essential life-skills in a normalised process – similar to that of children not in the care system -, by focusing on achieving good outcomes. In particular, family life, health and education are considered as being the key factors for the future integration of children and young people, so they are then fully able to contribute positively to society. The dilemma lays on the over-protective nature of many fostering and residential environments that was observed during the HHH programme. It derived from an often risk averse professional guidance and practice (Milligan, 2011), which provides restricted opportunities for children to grow and develop in the same way as their peers not in care. They have limited scope to experience activities that support their confidence facing daily challenges. This also hinders the process of gaining useful skills for a successful transition to independence and adulthood in the future.

On the other hand, a social pedagogical framework emphasises learning facilitated by everyday life activities and events, with age-appropriate risks seen as opportunities for renewed understanding and discovery. This is not ‘set up’, but it happens spontaneously as children are encouraged to help themselves, to be compassionate and empathetic, to work together as a team, thus learning key skills they will need for their future life as inter-dependent and autonomous adults. From a social pedagogical perspective, we speak of the notion of the ‘rich’ child (Malaguzzi; cited in Moss and Cameron, 2011), in contrast to the ‘child in need’ of dominant UK child welfare discourses, social pedagogy focuses on strengths and potentials, rather than deficits (Smith, 2012).

Another area that can further this understanding is that of the professional childcare sector, and how it has been differently constructed in countries that have a tradition in social pedagogy, compared to those who do not have the approach as part of the roots of their welfare systems. In most continental European countries, we find social pedagogues – in some countries known as social educators -, within multidisciplinary teams across the different areas of the social care system. For example, early years provision, youth work, working with children in residential care, schools, in resources for adults with learning or physical disabilities, working with disadvantaged groups, supporting the elderly or even in the business sector as wellbeing support for staff.

Another contextual difference in the professional sector is that in many continental European countries it is more common to have mainly residential provisions for children and young people in care; with fostering coexisting alongside but to a much lesser extent than it is used in the UK, where fostering is a common form of placement for the majority of children and young people that enter the care system. We can see this by noticing the percentage of children who are in a group-care type of placement across four countries: England, 14% (in 2010); Denmark, 47% (in 2007); Germany, 54% (in 2005); Italy, 48% (in 2007) (Ainsworth and Thoburn, 2013). It is important to note that perception and context of residential services across Europe varies. In most continental European countries, the staff in residential services have university degrees in social or educational sciences (for example social pedagogy or other relevant subjects such as psychology, teaching or social work) and are fully trained prior to working with a vulnerable population. The services are often seen as supportive rather than ‘last resort’ or ‘punishment for bad behaviour’. Germany has a variety of foster placements hence foster carer roles. If you want to provide a specialist, foster placement for children and young people with particular needs one has to have a qualification. However, this doesn’t apply to general foster carers.

At the time of writing this paper the UK system does not specify a requirement to have certain qualifications in order to be employed as a foster carer or as a residential care worker. The preapproval requirements for foster carers are national minimum standards; which practitioners have to demonstrate they can abide by and provide. After this, all foster carers have to complete the compulsory “Training Support and Development Standards for Foster Care” (TSD) within 12 months of being approved. Apart from these national requirements and the TSD, each organisation/agency/service sets their own priorities in terms of the knowledge they require their practitioners to have, usually in relation to specific models or approaches. In the experience of the HHH programme, some of the more common were attachment theories and restorative practice. Specific knowledge is offered through training or other learning opportunities. Scotland is in the process of adding mandatory training for foster carers and the Scottish Social Service Council is in the process of revising and adding mandatory training for residential staff. At the time of writing this paper, it has not yet been established.

“The research showed that, in England, children in residential care have more severe and disturbed backgrounds than in the other countries studied. Yet the training and education of staff in England is at a much lower level than in those countries” (Petrie et al, 2005:5).

This part of the paper will explore the integration of the two cultural approaches, focusing on how social pedagogy and social work can jointly contribute to the quality of care in the UK. Firstly, it looks at how quality of care is understood within the British context, and then it explores the relevance of a shared value base by practitioners. Following this, how the organisational and managerial levels can be aligned under a social pedagogical way of working is examined. The final aspect explored is how the different focus on processes and outcomes under the social pedagogy lens and the pivotal role of relationships can be integrated into practice.

There is not a shared definition of quality of care in the British context. As mentioned above, to be approved as a foster carer depends on fulfilling the national minimum standards and the criteria established by each organisation or agency. The result of this diversity is that there are multiple definitions of what makes good quality foster care or what is needed to work in fostering. Having said that, there are some commonalities as there is a large percentage of organisations that use The Fostering Network ‘Skills to foster’ training and often Coram BAAF’s (Adoption and Fostering Academy) assessment tools which gives a more united approach to the pre-approval process and means that the preparation training has a very similar baseline across these organisations. At the same time, the British institution of fostering and adoption panels each comprises a diverse team of professionals, enabling a consistent and comprehensive approach to foster carer’s approval. National organisations like The Fostering Network and Foster Talk enable connectivity through their national campaigns, up to date online resources as well as a helpline for foster carers. Other unifying criteria are the reference guides for the standards of working with children: “Every Child Matters” for England and “Getting it right for every child” in Scotland.

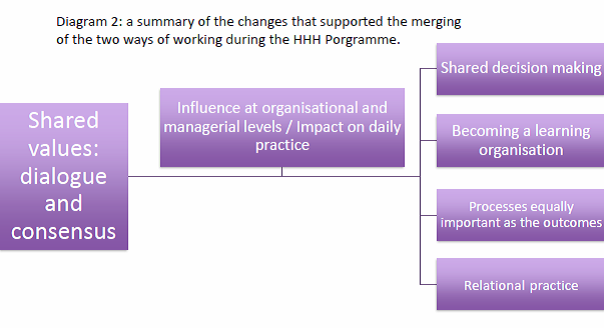

From their experience in the HHH demonstration programme, the social pedagogues found that by integrating social pedagogy into the working culture of the different organisations involved, some key elements of the approach were particularly useful and became valuable agents of change. Some of these elements are explored here, some other aspects (the different approach to risk, the relevance of reflective practice), will be analysed in the mentioned future paper.

Social pedagogues consider important to share a clear and unified value base with those who they work with, this serves as a reference to sustain and guide practice for practitioners sharing a working environment or professional responsibilities with a specific group. When a social pedagogue makes decisions, she has to use value-based assessments, combined with theory applied to her practice through reflection in action, and this is done in dialogue with others, the client and the other colleagues or professionals. It is rather about ethics and values than methods and techniques (Storø, 2013). Thus, social pedagogy is a combination of theory, research and Haltung. During the HHH programme, the social pedagogues noticed a need for further dialogue around the value base of practice. This situation contributed at times to a certain degree of inconsistency in practice that was also a result of the confusion over continuing governmental changes and political and financial agendas brought to the field.

It is relevant to note that all qualified social workers in the UK have a code of practice and ethics. From the experience throughout the programme, there can be different understandings of these shared values, or how to put them into practice, or assumptions of the kind ‘we all think the same’. Ongoing dialogue and reflection could be a useful resource to explore this more thoroughly. Constructing a shared ethical foundation is one of the best investments for the future that can be made in order to support coherence and stability in decision-making processes for children and their families.

Social pedagogues value practicing in organisations with flat hierarchies and to have an inclusive and democratic leadership. This is practiced by leaders by actively seeking employee’s opinions and input into decisions. They provide space and resources for co-creating processes and encourage employees to be autonomous. An example can be found in some continental European residential care settings “where the norm is democratic decision making within relatively flat hierarchies, allowing staff to take on a higher level of responsibility, commensurate with their qualifications” (Cameron et al. 2011: 9). However, social pedagogues also recognise the need for management, for someone to make a final decision. It is not easy to find the right balance between employee participation and management. Ideally, they go hand in hand.

Important organisation wide decisions are made in dialogue between leadership and staff. Both parties help each other to keep the basic principles of the organisation alive. These principles are outlined in the service concept written by leadership and staff together. This not only involves the whole team it also increases the willingness to live up to the concept. In Britain, the HHH social pedagogues saw that the direction and principles of their organisations were often decided by the management and then handed down to all employees to realise them. In some of the organisations, social pedagogues had no input into these. This made it difficult for many staff members to identify with these values and to actively promote and own them.

.jpg)

Accepting challenges and conflict leads to more open, transparent and dialogical communication within the system by sharing decision making equally between professionals, parents, children and young people. The participation of children and young people in decision making in social pedagogical thinking is observed at all times, because the social pedagogues are working according to the principle of helping people to help themselves (Storø, 2013). In other words, social pedagogy works towards creating the context that facilitates empowerment. Social pedagogues would explore a wide diversity of strategies to include the child’s or young person’s voice in decision-making processes about their lives. Children’s social workers will also strive to make the children’s voice heard in the decisions that are made about their life. The main difference is – from the HHH programme’s social pedagogues’ point of view – that the system is not always conductive to bringing the child’s wishes to the table, or that the consultation processes and participation in decision-making can be a rather tokenistic exercise. This also applies to including the parent has and foster carer’s views, particularly when they can be systematically excluded from the process.

A shared aim in the UK foster care is to be able to retain foster carers and social work staff, and it is expected that they develop professionally. It was found that in the field of fostering there are many training opportunities available for foster carers and professionals. While one HHH site encouraged foster carers to write reflective accounts about the training they attended, the majority did not check if and how the newly acquired knowledge was linked to practice. There are high expectations placed on how foster carers meet care standards, but at the same time, they are often not seen as professionals on an equal stance with social workers and other practitioners, being required to be very flexible and engaging in what they do, with the main focus in evidencing the outcomes of children in their care.

Social pedagogy can support the emphasis in quality of learning and training, making connections between theory and practice through reflection, following up with experiential sessions or ‘reality tests’ and reviewing the knowledge afterwards. This promotes a bigger possibility for embedding whatever learning has been promoted in their daily practice. Learning and development needs to be on an ongoing basis. The social pedagogues experience in the programme shows that this approach to training directly supports the retention of foster carers and staff, because it allows people to make mistakes and learn from them. There is not a right or wrong way to do things or a universal solution for their challenges, there are just stages in a learning journey, and therefore there is no need for blame.

Cameron (2016), in her meta-analysis of several evaluation reports, identifies that social pedagogy learning and development initiatives offer the opportunity for the workplace to see itself as a ‘learning organisation’, where practitioners are more reflective, and give more time and relevance to their own and the client’s learning. The conceptualisation of a learning organisation here, relates to where “learning is valuable, continuous, and most effective when shared and that every experience is an opportunity to learn” (Kerka cited in Smith, 2001, 2007).

The process as important as the outcomes

There is wide recognition of the relevance of outcomes to monitor and evaluate the quality of care provided in the UK’s foster care practice as well as in social pedagogical traditions. However, the ‘how’ to achieve this differs. In mainland Europe, the idea of Immanuel Kant is widely spread in the working approach. His message is that an action is justified if it is in accordance with specific, socially approved moral principles. In contrary, the British/American approach gives a certain liberty to professionals and institutions to follow the principle that a good outcome can justify even a questionable process to get there (Merkel cited in Engel, 2016).

.jpg)

The British social care system can be highly procedural. The working practice of professionals is supported by a huge amount of procedures and policies, which they have to apply and evidence to be considered as providing a good standard of care by the governmental inspection bodies. Attention to appropriate procedures is a necessary part of the work, but should not become its basis (Petrie et al. 2009). In the UK there is some form of guidance for nearly every possible situation, event and circumstance. New developments, like the rise of e-cigarettes or tablet computers, are answered with new procedures and/or policies to be followed by all employees.

In social pedagogy, every situation is seen in its uniqueness, which requires a unique response. “The professionalism of the worker, transparency of practice, a commitment to team work and accountability to others in the team, are seen as the best guarantee of child safety” (Petrie et al. 2009:7). There is a holistic understanding of care and development, by bringing different theories together in a journey of permanent learning. This contrasts with a way of working based on the idea that ‘one model fits everyone’. Moreover, pathologising approaches have come to dominate social work practice in the UK (Lonne et al, 2009; Munro, 2011). Social pedagogy uses a variety of models and theories and brings a holistic approach to the table, considering the individual needs in interaction with the wider context, the environment and the specific circumstances. As a result, outcomes are established from synchronic and diachronic analysis, where everything is seen as interconnected and practice is sustained by meaningful relationships. This way of working supports children’s development and empowerment, acquiring a set of emotional, social and life skills that will impact positively in their wellbeing and will help them to achieve a fulfilling independence in the future.

.jpg)

Social pedagogues would regard the process to be equally important as the final outcomes. They believe that when the process is effective then outcomes are likely to be beneficial, it is not possible to disentangle the two (Smith, 2012). When the outcomes are looked at in a compartmentalised manner, treated separately in measurements that evidence different areas of the child development, the process can easily become a box ticking exercise, with a strong focus in documenting and measuring the final output. Instead of documentation, recording and measurement, the use of self-reflection and self-awareness are the key skills of the work in social pedagogy. At the same time, every work place requires documentation and recording, this is a very useful tool to monitor and reflect on the process, but as mentioned above, it should not be the main part of the work. There is not a ‘tool box’ or a policy that tells you what to do in each circumstance, the professionals use reflection on an ongoing basis, thus there are not universal solutions and mistakes become learning opportunities. In social pedagogy, conflicts are considered an important part of the journey, an inevitable part of it, not something to be avoided. They represent a necessity for progress because they bring a chance to grow, develop, change what is not working and gain new learning that can be useful for the future (Kleipoedszus, 2011).

Social pedagogues are equipped throughout their studies with a wide range of theories from social and educational science, as well as creative/practical activities they can engage in with their clients. These range from art therapy to outdoor education. British social work students learn to use different tools like the ‘Three Houses Child Protection Risk Assessment Tool’ from the Signs of Safety Approach (Bunn, 2013). These tools are used for example to collect the views of a young person on events in her life in a child friendly way. They are mostly used in only one session. It takes considerably longer to undertake for example a process of creative work or an outdoor activity with a client. Social pedagogues noticed that their British colleagues’ workloads did not enable them to engage with clients in such an intense form of intervention. In addition, due to the financial climate and current financial crisis funding was limited for activities (Local Government Association, 2014).

Another difference is the compartmentalisation of responsibilities in working with clients, per example social workers only writing assessments or only supporting approved foster carers, which can build barriers in applying the holistic working approach of social pedagogy.

Nevertheless, the experience of the HHH programme proved that it is possible to integrate a social pedagogical approach within the way of working in the British system. The social pedagogues experienced that when working in an equal partnership with their social worker colleagues they could reach a well-planned and clear-shared structure. Everyone knew what was expected from them, there was a framework where the flexibility and holistic perspective of a social pedagogical approach could thrive. When there was trust within the team, clarity would stem from that, and there was openness for the reflective and creative elements of social pedagogy.

It is worth mentioning that there are areas in the UK foster care practice that were considered very valuable by the HHH social pedagogues. One is the use of interdisciplinary panels to, for example, evaluate the quality of matching processes[3], another is the importance of having delegated authority[4] in place for each foster child, and in Scotland through ‘Getting it right for every child’ with its strong focus in the wellbeing of children. These are many examples of how social pedagogy fits with existing policies and how British ideas and conditions can nurture a social pedagogical way of thinking.

Relationships at the centre of practice

In the wider Anglophone context, there has been a tendency to a strict delineation of personal and professional relationships. Consequently, the importance of relationships became hidden behind increasing recourse to technical and managerial ways of working. However, recent years have seen a resurgence of interest in relationally based practice in the social work literature (Smith, 2012). Some authors go further in using the notion of ‘relational practice’ described as ‘being in relationship’, which is different than, and preferable to ‘having a relationship’ (Garfat, 2008).

“Being in relationship means that we have what it takes to remain open and responsive in conditions where most mortals and professionals quickly distance themselves, become ‘objective’ and look for the external ‘fix’.” (Fewster, G. 2004 cited in Garfat, 2008: 7).

In this context of an increased acknowledgement of the importance of relationships shared by the UK foster care with social pedagogical thinking, there is a need to be able to put relationships at the centre of practice by setting the value and quality of the relationships at the heart of what we do. Munro (2011) argued that the necessary centrality of relationships for high quality child protection practice had become obscured in organisationally driven, rational technical approaches in social work.

The experiences in enhancing relationships in social pedagogy practice from the HHH programme exemplify what Claire Cameron’s paper ‘Cross-National Understandings of the Purpose of Child-Professional Relationships’ identifies as the four different purposes in how social pedagogues conceptualise relationships:

“Supporting a child in developing skills and a sense of self; creating the conditions for an ethical encounter between the professional and the child, characterised by ‘being there’ for the child; providing opportunities for the child to be involved in decision-making and democratic processes; and gaining an understanding of the child’s lifeworld and the challenges experienced by the child.” (Cameron 2013 cited in Eichsteller & Petrie, 2013:1).

Social pedagogy as a child-centred and strength based approach focuses on the process and meeting the children where they are at, without being prescriptive and setting the starting point on where the child should be. In procedural driven practices, the foster carers/residential workers would apply their ‘tool box’. They would do things ‘to’ the child in order to achieve the outcomes that the professional team has established often based on where the child ‘should be at’. Social pedagogy instead suggests doing things ‘with’ the child for building a positive and meaningful relationship, supporting the child or young person to develop their own journey in care and beyond.

The HHH’s social pedagogues advocate for merging social pedagogy with the UK system; at organisational level by looking for a major balance between control and trust, as well as between the different roles and by sharing responsibility in decision making processes. This would be a prerequisite to dilute or minimise the impact that the culture of blame can have in how decisions are made in the system around the child, which affects all hierarchical layers. The dilemma lays on the fact that where there is a blame culture the system becomes reactive, and there is no room for learning or reflecting, so how could it be possible to make it better in order to avoid the same mistakes in the future? The social work profession has developed a ‘fear of failure’ and as professionals, they experience vulnerabilities with far reaching implications (Shoesmith, 2016). When the responsibility of the decisions are shared by the whole system – the professionals as well as the client – mistakes or problems are shared and can be seen as learning opportunities, each situation can be carefully analysed, thus solutions and consensus can be found.

In the United Kingdom as well as in continental European countries the pursuit is that children in care can thrive and have an environment that allows them to be able to experience similar levels of wellbeing as the rest of the children in society. The social pedagogues from the HHH programme argue the ‘what’ is the same; what differs is the ‘how’. A social worker who participated in the HHH programme expressed this as follows: “what I have valued from working within a social pedagogy model is how it enables you to focus on the quality of the relationships on a personal basis and also within the wider agency. Also how it uses a creative and holistic approach that puts the young people at the heart of the interventions”. The holistic approach, valuing the process so the way becomes also the solution, being action focused and strength based are fundamental aspects in social pedagogical thinking. Merging the two ways of working proved as not just possible in the different agencies who were part of the HHH programme, moreover, in some of them has become integrated in their way of working and has changed their organisations deeply.

.jpg)

Many organisations, academics and practitioners have been striving to introduce social pedagogy in the UK during the last years. A product of their work is that social pedagogy has become a relevant working practice on the agenda of an increasing number of organisations and local authorities around the country. Great effort and commitment will still be necessary at many levels to take social pedagogy forward and to see it becoming an integrated discipline in the social and educational fields in the UK in the future.

The paper has been writing with contributions and feedback from the HHH social pedagogues Marta Blanco, Stefanie Dorotka, Martina Elter, Manja Golobic, Rute Gonçalves, Christina Ketzer, Anne Kunz, Niina Robinson and Christine Spurk. Special thanks to Svend Bak, Lotte Junker Harbor, Liliana Santos and Jutta Weber for their support.

Ainsworth, F.; Thoburn, J. (2013). An exploration of the differential use of residential child care across national boundaries. In International Journal of Social Welfare, volume 23, number 1, p. 16-24. Retrieved from link [05.10.2016]

Boddy, J.; Cameron, C.; Moss, P. (2006). Care Work: Present and Future. London: Routledge

Bunn, A. (2013). Signs of Safety in England. NSPCC. Retrieved from link [9.11.2016]

Cameron, C.; Petrie, P.; Wigfall, V.; Kleipoedszus, S.; Jasper, A. (2011). Final report of the social pedagogy pilot programme: development and implementation. London: Thomas Coram Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London. Retrieved from link [26.03.2016]

Cameron, C. (2013). Cross-national Understandings of the Purpose of Professional-child Relationships: Towards a Social Pedagogical Approach. In International Journal of Social Pedagogy, volume 2, number 1, p. 3-16. Retrieved from link [24.11.2016]

Cameron, C. (2016). Social Pedagogy in the UK today: findings from evaluations of training and development initiatives. In Pedagogía Social. Revista Interuniversitaria, volume 27, p. 199-223. DOI: 10.7179/PSRI_2016.27.10 Retrieved from: link

Doyle, M. E.; Smith, M. K. (2007). Jean-Jacques Rousseau on education, the Encyclopaedia of informal education. Retrieved from link [21.05.2016]

Eichsteller, G.; Petrie, P (2013). Editorial: Relationships that Matter.In International Journal of Social Pedagogy, volume 2, number 1, p. 1-2. Retrieved from link [24.11.2016]

Eichsteller, G.; Holthoff, S. (2011). Social Pedagogy as an Ethical Orientation towards Working with People – Historical Perspectives. In Children Australia, volume 36, number 4. link Retrieved from link [27.10.1016]

Eichsteller, G.; Holthoff, S. (2012). The Art of being a Social Pedagogue. Developing Cultural Change in Children’s Homes in Essex. In International Journal of Social Pedagogy, volume 1, number 1. Retrieved from link [24.11.2016]

Entwistle, H. (1970). Child-Centred Education. London: Routledge

Garfat, T (2008). The inter-personal in between: An exploration of relational child and youth care practice. In G. Belleville & F. Ricks (Eds), Standing of the precipice: Inquiry into the creative potential of child and youth care practice (pp. TBA). Edmonton. AB: MacEwan Press

Griffin, E. (2014). Child Labour. Discovering literature: Romantics and Victorians. British Library. Retrieved from link [20.05.2016]

James, A.; Prout, A. (2015). Constructing and Reconstructing Childhood: Contemporary issues in the sociological study of childhood. Abbingdon: Routledge

Kleipoedszus, S. (2011). Communication and conflict: An important part of social pedagogic relationships. In Cameron, C.; Moss, P. (Ed.) In Social pedagogy and working with children and young people, p. 125-140. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers

Local Government Association (2014). Under pressure: How councils are planning for future cuts. Retrieved from link [09.11.2016]

Lonne, B.; Parton, N.; Thomson,J.; Harries,M (2009) Reforming Child Protection. Oxon: Routledge.

Engel, P (2016). Interview with Reinhard Merkel about the topic “philosophy of law”. In: Der Tag (18:00 – 19:00), HR2, [03.02.2016]

Milligan, I. (2011). Resisting risk-averse practice: the contribution of social pedagogy. Children Australia, volume 36, number 4, p. 207 – 213. link [04.05.2016]

Moss, P. (2010). What is Your Image of the Child? In UNESCO Policy Brief on Early Childhood. Number 47. United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation. Retrieved from link [21.11.2016]

Moss, P.; Cameron, C. (2011). Social Pedagogy and Working with Children and Young People: Where Care and Education Meet. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Munro, E. (2011). The Munro Review of Child Protection: Final Report: A Child-Centred System. London: Department of Education. Retrieved from link [06.04.2016]

Petrie, P.; Boddy, J.; Cameron, C.; Heptinstall, E.; McQuail, S.; Simon, A.; Wigfall, V. (2005) Pedagogy – a holistic, personal approach to work with children and young people, across services: European models for practice, training, education and qualification. Unpublished briefing paper, Thomas Coram Research Unit, Institute of Education University of London. Retrieved from: link [11.04.2016]

Petrie, P.; Boddy, J.; and Cameron, C.; Heptinstall, E.; McQuail, S.; Simon, A.; Wigfall, V. (2009). Pedagogy – a holistic, personal approach to work with children and young people, across services: European models for practice, training, education and qualification. Updated briefing paper, Thomas Coram Research Unit, Institute of Education. University of London. Retrieved from: link [28.05.2016]

Petrie, P.; Chambers, H. (2009). Richer lives: creative activities in the education and practice of Danish pedagogues: a preliminary study. A preliminary study: report to Arts Council England. London: Thomas Coram Research Unit, Institute of Education. University of London. Retrieved from: link [12.11.2016]

Petrie, P.; Boddy, J.; Cameron, C.; Simon, A.; Wigfall, V. (2006). Working with Children in Care: European perspectives. Buckingham: Open University Press

Richardson, R. (2014). Foundlings, orphans and unmarried mothers. Discovering literature: Romantics and Victorians. British Library. Retrieved from link [20.05.2016].

Shoesmith, S. (2016). Learning from Baby P. The politics of blame, fear and denial. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Smith, M. K. (2001, 2007) ‘The learning organization’, the encyclopedia of informal education. Infed. Retrieved from link [22.05.2016]

Smith, M. (2012). Social Pedagogy from a Scottish Perspective. In International Journal of Social Pedagogy, volume 1, number 1, p. 46-55. Retrieved from link [18.10.2016]

Stein, P. B. (2007). Being the Change: Becoming Agents of Personal and Cultural Transformation. Doctorate Dissertation, Pacifica Graduate Institute

Storø, J. (2013). Social Pedagogy Practice. Bristol: Policy Press

Thiersch, H. (2005): Lebensweltorientierte Soziale Arbeit. Aufgaben der Praxis im sozialen Wan-del. 6. Aufl. Weinheim, München, Juventa

White, M. (2014). Juvenile crime in the 19th century. Discovering literature: Romantics and Victorians. British Library. Retrieved from link [20.05.2016]

[1] Germany, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain, Finland, Austria, Sweden and Denmark

[3] Matching the child with a placement that matches their assessed needs.

[4] Delegated authority is the process that enables foster carers to make everyday decisions about the children and young people they care for, where that authority has been delegated to them by the local authority and/or the parents.